For years I’d been intrigued by the peculiar house on Chang’an Rd in Taichung’s Taiping District. As with most of my best discoveries in Taiwan, I’d stumbled upon it – in this case almost literally, when a scuffed pass had sent a football trickling down a sloping, paved path leading out of the south side of Liyuan Park, a jagged patch of green just south of the confluence of the Dali and Buzi rivers.

My presence here was itself purely down to chance: I was in Dakeng visiting a friend who had become temporarily occupied with business matters, so I scooted off with my then 10-year-old son to explore the environs.

The misplaced ball came to a stop at a knee-high brick wall at the end of the slope, which was designed to prevent vehicle entry to the park, and I lumbered off to retrieve it. Bending down to pick it up, I noticed a strange pattern on the façade of a building at the end of the adjoining lane. Much to the lad’s annoyance, I decided to embark on a customary poke around.

As I approached, it became clear that this was something remarkable. Aside from the grand, motif emblazoned on the front that had attracted my attention, the contents of the yard made it obvious that this was the home or studio of an artist – more specifically a sculptor.

Dozens of effigies occupy the wide-open space around two buildings. The breadth of styles, materials and subjects bespeaks a concerted eclecticism. In a corner, under the central façade, lurks a sturdy Sun Yat-sen, one pocketed hand ruffling the tail of his greatcoat, the other sandwiching a book against a concrete post. Immediately to his right is a free-form swirl in bronze that looks like a calligraphic doodle.

Elsewhere, golden schoolgirls peep from behind pillars, mangled iron abstracts evoke industrial menace, and indigenous archers aim at unseen prey, flanked by faithful hounds whose keen gaze anticipates the trajectory of the primed projectile.

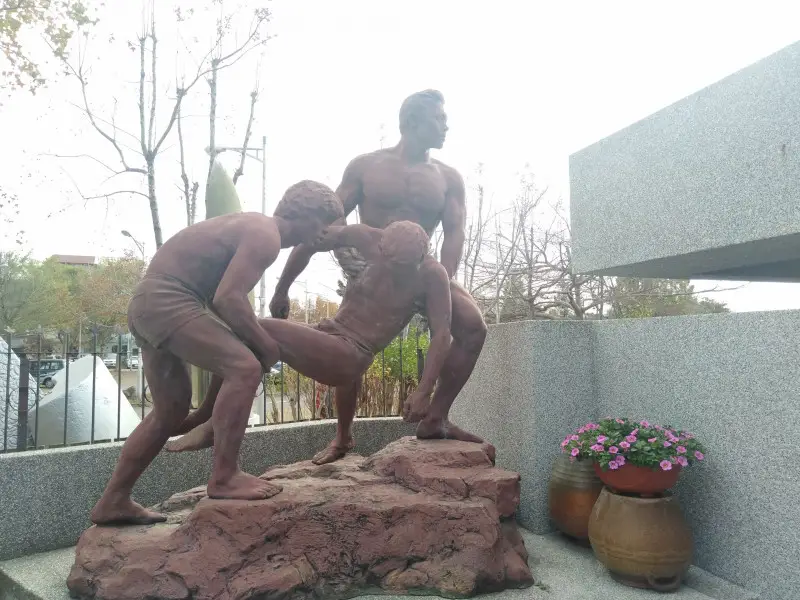

Some of the figures are familiar – a lithe, cherry-breasted lady with bulbous hips and Modigliani-esque elongated limbs is immediately recognizable as a replica of a work that stands outside the south entrance of Taipei Fine Arts Museum. Another clay-colored bronze of two muscular men, stripped to the waist, carrying a third limp form across a craggy slab of rock, I cannot quite place.

Many of the representational statues appear to depict friends, family, and public figures. Interspersed with the more abstract works are zen garden-type rocks and crooked bonsai trees. The disparate elements somehow work together, combining to create a spectacular but serene whole.

I try the buzzer at the gate in front of the building to the right. Minus the ornate façade and corrugated iron-walled annex – and even this quintessentially Taiwanese tacked-on tackiness is tastefully rendered in a cream that pairs with the varnished wooden slats on the side – the two-story construction is smaller and far less remarkable than its partner.

Still, the relative lack of grandeur is more than compensated for by two works perched on pillars either side of the building, next to the gate. To the left is a large bronze of a sturdy peasant clad in a conical rice hat and straw cape, one of the shoulder flaps lifted to shelter a scrawny adolescent. The farmer motions to an unknown point in the distance, presumably a destination where the pair will find respite from the impending storm. On the other side, a pair of undulating squiggles look like electrified eyebrows.

A sign on the gatepost refers to someone named Lee Li-hua. A quick Google provides two possibilities: a gorgeous Shaw Brothers starlet who had died aged 92 several months prior or – slightly more likely – a KMT Taichung City Councilor. Closer inspection of the sign shows the latter is indeed the case, but that, oddly – my son informs me – this is just a contact address for said politician, rather than her residence.

This was summer 2017. No one appeared to be home during my first visit, nor when I tried a second time while down again from Taipei for a Christmas bash. Third time lucky, some time in spring the following year: A chirpy, silver-haired lady finally opened the gate, presented me with a name card and informed me, with visible pride, that her husband was the creator of the treasures in the yard. I told her I’d be in touch soon, but then – as is frustratingly far too often the case – got sidetracked and misplaced the card.

It wasn’t until this time last year, as I set out on a cross-island bicycle trip – something of a tradition in recent years – that I thought about finally trying to get hold of this craftsman, whose name I couldn’t even remember. Thanks to some last-minute legwork from an old pal – GuanXi’s own Michael Schram – I was furnished with a website, phone number and name for the mystery maestro.

Hsieh Tong-liang, I discovered, as I read through his online biography, is not only one of Taiwan’s most decorated artists, but also an acclaimed tai chi practitioner who has established his own school. Indeed, as I was soon to learn, Hsieh sees a symbiosis between his two lifelong passions and, with the help of his daughter and agent Diane, has striven to realize the precepts of the martial art in the fluid forms and ying-yang contrasts of his work.

While spending the night under a bridge near the Shuiyun Waterfall trail in Tai’an Township, Miaoli County, on an abortive mission to find an obscure photographer, I receive Michael’s message confirming he has wangled Mr. Hsieh’s details from a neighbor. I head down to Dakeng via the Liyutan Reservoir and Zhuolan Township at a leisurely pace, arriving late afternoon the next day.

The following morning, I try the number from my hotel, more in hope than expectation. Regardless of the outcome, I’m planning to keep riding south today, so my window is limited to the next few hours. In my experience, the pushiness perceived in a spontaneous interview request rarely gets results in Taiwan, so I’m pleasantly surprised when Diane tells me her dad is happy to see me after lunch.

When I’m finally let through the portals, my immediate inclination is to explore every nook and cranny of the yard. Like an adolescent at an amusement park with too many attractions to take in at once, I don’t know where to start.

My starry-eyed wonder does not go unnoticed. “Come in, come in,” says Diane, ushering me to the house. “Take your time. My father will introduce all these works later.”

Master Hsieh greets us at the open front door. “Hello. This is the Englishman? Come in. Drink some tea.”

Father and daughter are clad in matching black tangzhuang-type tops, loose pants and baseball caps. Rather than the silk, cotton, or linen of the more traditional tangzhuang jackets, the material here resembles the quick-dry polyester favored by athletes. The gray trim of the stiff collar matches two, largely ornamental, button-knot fasteners just above a patch pocket.

The front of the shirt features a stylized figure holding a tai chi pose. I later learn that this is a crouching “dragon” form represented in several of Hsieh’s recent Kung Fu series of works. Hsieh’s signature accompanies the image. On the back is a large logo comprising the characters for Taiwan, which have been rendered into the shape of the island. It bisects a smaller set of characters reading “Chen Style Taijiquan Association.”

This organization, which also goes under the name of the Taiwan Chen Style Taijiquan Development Association, was founded by Hsieh and continues to operate under his tutelage. Having taken up the martial art at the relatively late age of 38, Hsieh has won national competitions in the traditional forms category and, latterly, served as a judge and commentator at major international tournaments. He’s also President of the Chinese Taiji Bagua Association and a high-ranking instructor in that discipline – baguazhang being one of the three main neijia or “internal” Chinese martial arts, along with tai chi and xing yi quan.

Diane explains that she assisted with the design of the outfits, and it soon becomes apparent that the emphasized overlap between Hsieh’s artistic creation and physical performance is as much about shrewd marketing on her part as an overarching philosophy on his. And there’s no doubting it’s a clever strategy: With his trendy uniform, impeccably maintained, silver whiskers and sideburns, and the trilby that usually occupies the place taken by today’s cap, Hsieh looks every inch the contemporary kung fu sage.

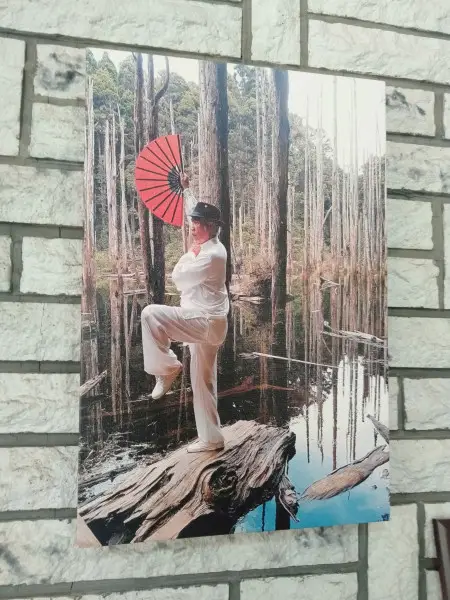

Photographs and paintings around the house reinforce this assiduously cultivated image – most notably a portrait in the living room of Hsieh adopting the “Golden Rooster Stands on One Leg” pose. (Think Karate Kid crane kick, here.) Poised on the edge of a half-submerged log, with a flooded forest of denuded pines forming the backdrop, he holds aloft an open fan with blood red leaves, separated by thick, black ribs. Contrasting with Hsieh’s loose, cream silk attire and a quiet patch of crystal lake that reflects the treetops, the elegant violence of the fan and the pose present a scene that is both mesmerizing yet slightly contrived.

“That was taken in Xitou, Nantou County,” says Hsieh. “It’s extremely beautiful and peaceful up there. You should definitely go.” At first, I’m confused. He seems to be referring to Xitou Nature Education Area, which is close to Xitou Monster Village, a kitschy tourist sport that – pre-Covid – attracted hundreds of thousands of kawaii diehards each month. Fun, but hardly a bastion of serenity.

The scenery looks familiar, and a subsequent, surreptitious reverse image search reveals the location is in fact Shuiyang Forest. This is often described as being part of Shanlinxi Forest Recreation Area (also transliterated as Sun Link Sea Forest Recreation Area – in Zhushan Township, but from what I can determine is just across the border in Chiayi County’s Alishan Township).

This lake and wetlands area was created by the 921 Earthquake in 1999, and while I read about it in my first few months here courtesy of the late Robert Storey’s 2001 Lonely Planet Taiwan guide, I’ve still not made it up there – something I hope to remedy one day.

As we sit and take tea in the living room, my attention turns to an artwork on the back wall above the sofa where Hsieh sits. “Very special, right?” asks Diane rhetorically. And it is.

“That’s Chen Ting-shih,” she informs me. “If he’d lived in Paris, he would’ve been just like Picasso. He combined calligraphy, painting, iron sculpture … he could do pretty much anything.”

The image is simple but striking: a white calligraphic zigzag on a black background. In the bottom left-hand corner, a Japanese-style rising sun is set against a thick band of white that resembles a bleak snowscape. Completing the effect, a haze of powder rises on the horizon.

I’m embarrassed to admit I’ve never heard of the artist. “Oh, then you really must visit the memorial hall,” Hsieh says, with a sudden burst of lively gesticulation, at odds with his typically phlegmatic disposition. “It’s very close to here, in an old tobacco factory. Can you find the address for him, Mei-huang?”

Diane obliges, and it turns out that the Chen Ting-Shih Memorial Art Museum (at Taiping Tobacco Market) is right on my route south to Wufeng District later that afternoon. The recommendation was bang-on: This is one of the best small art museums you’re likely to find in Taiwan, with works across a range of media, by a giant of Chinese/Taiwanese art.

Chen’s life and career, which comprised several distinct phases, including a period as woodcut printer and cartoonist, when he was known under the pseudonym “Ears”. make for fascinating reading.

As the founder of the short-lived Taichung-based Peace Daily magazine, Chen frequently satirized corrupt officials, but was eventually forced to step back from political commentary when the KMT government began cracking down on even the mildest dissent. His fellow printmaker Huang Rong-can, whose work had appeared alongside Chen’s in various publications, also attempted to deflect official scrutiny by refocusing on indigenous themes but was not as fortunate: He was executed on trumped-up charges in 1952.

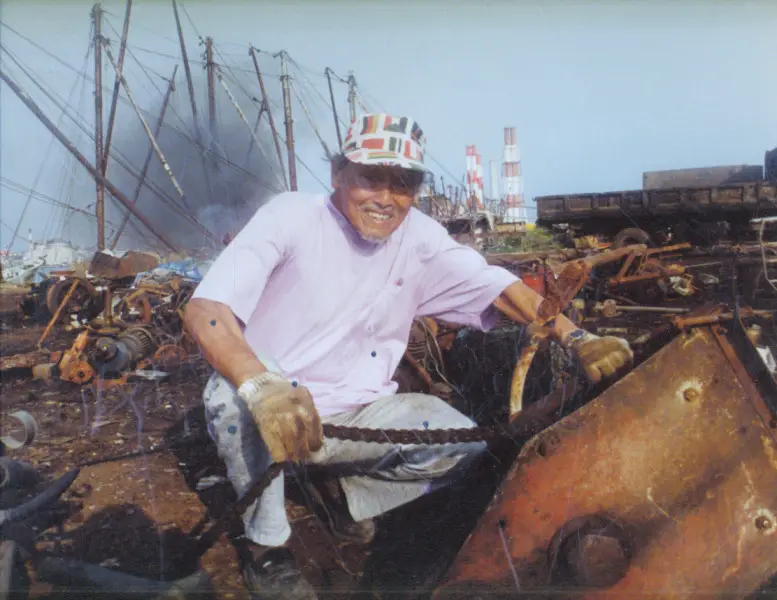

For most of the next decade, Hsieh remained inactive, before remerging as an abstract expressionist painter. In the late 1960s, he reinvented himself once more, this time as a found-object sculptor.

“He was a true master,” says Hsieh. “A genius, who I am proud to call a friend and mentor.”