By James Baron

From the top of a hill in Beitou District, Guanyin's benevolent eye cuts through the sulfurous fug. The Goddess of Mercy is a ubiquitous presence at places of worship in Taiwan, but her role as the resident deity of Puji Temple – one of Taipei's finest colonial relics – is a little less run-of-the-mill. Inquisitive tourists will learn that she serves as the guardian of Beitou's hot springs. Dig a little deeper and you might discover that she has been saddled with a more onerous responsibility – one that remains a lurid testament to the intersection of sex and purgatory in colonial Taiwan.

Despite an official ban on such services in 1979, as Taipei's premier red light district, Beitou continued to offer carnal delights until the early '90s. It might seem strange that the advent of democracy coincided with a crackdown on prostitution but, while the motivation was more about cleaning up the city's image than any human rights considerations, it was probably the right decision. Under Japanese rule, sex workers were essentially slaves and, right up to the end, there was little in the way of choice that exists in countries with properly regulated industries.

As the goddess of mercy, Guanyin was historically a compassionate guardian of socials outcasts, including sex workers. So the goddess in the Puji Temple served a dual function as protector of the springs and the women who used to ply their trade at the resorts there. More interesting, though, is the presence of another, less common semi-deity, housed in a small pavilion to the right of the temple.

This chunky granite statue is a representation of the Dizhangwang Pusa (地藏王菩薩), literally the “Earth store”or “Earth womb.”Better known in the West by his Sanskrit name Ksitigarbha, he is revered in Japan as the guardian of lost souls, particularly stillborn and miscarried babies or aborted fetuses. For this reason, in the Japanese tradition, he is commonly depicted holding children in his right hand or sometimes wrapped in his robe, to hide them from the demons who would condemn them to perpetual hard labor as punishment for failing to accumulate sufficient beneficence in their fleeting existences. On his forehead, there is often a small dot that might be mistaken for a bindi. In fact, it's a third eye that bespeaks a perspicacity that transcends darkness and light. His left hand clasps a staff for prising open the gates to the underworld, a most appropriate utensil at Beitou, given his proximity to a popular tourist attraction nearby, the literal hotspot known as “Hell's Valley.”

In Taiwan, in the rare instances he is encountered – at Sun Moon Lake's Hsiangde Temple, for example – he invariably clutches an orb or gem of some sort in his right hand, in lieu of an infant. This is said to light up the darkness of the Dantean neither-here-nor-there netherworld he inhabits. Yet, overlooking the former den of iniquity at Beitou, he is once more depicted cradling a baby in the crook of his arm. Of course, as Puji is a Japanese temple, the reversion to this more orthodox representation might not seem that surprising. But there's actually a more sombre reason at play: Here, Ksitigarbha is watching over the souls of the uncounted aborted fetuses, unwanted by-products of the century-long flesh trade.

From the days when they were serving military men – kamikaze pilotsbefore their last fateful sortieand, later, U.S. servicemen enjoying a little R&R– to the tail-end of the martial law era, when a much more quotidianclientele made up the bulk of their custom, most of the girls working in the Beitou red light district were aborigine. Although many of these were from “raw”, high-mountain tribes, quite a few would have been of Pingpu descent.

These were the plains aborigines with whom Taiwan's colonizers – Dutch, Spanish and Chinese – historically enjoyed relatively stable interaction. Because of their propensity for Sinicization, they became know as the “ripened” or “cooked” (as it is more commonly rendered in English) aborigines. The Pingpu of Beitou were one of the various groups that have been lumped under the general designation Ketagalan (凱達格蘭).

The name for Beitou, which allegedly meant “witch” in reference to the bubbling, misty springs comes from the now extinct Ketagalan tongue (Kipatauw) by way of the Southern Min language, commonly referred to as Taiwanese (Baktau). While they were much more receptive to outsiders – Han Chinese, European or other plains tribes – than the “raw” mountain tribes, they were still more than capable of a good old-fashioned atrocity when it suited them.

It seems that the early hospitality the Danshui-based Senarclan displayed to the Spaniards was probably a ruse to play them off against the rival Pantao group over the river in Bali District. And despite being perennially engaged in internecine skirmishes, the two clans weren't averse to putting their quarrels on hold to gang up against the interlopers. Following the back-to-back murders of two priests in 1636*, the two tribes apparently joined forces to attack the Spanish at the original Fort San Domingo in Danshui**.

Spanish reprisals saw the various Ketagalan groups scattering, with two small clans ending up in Beitou and becoming known as the Neibeitou and the Waibeitou tribes (“inner Beitou” and “outer Beitou” respectively) These groups were involved in intermittently in uprisings against the Qing Dynasty regime, which governed with varying degrees of control Taiwan from 1683 to 1895.

In 1699, two notable rebellions occurred, the second of which saw the Neibeitou group cooperating with the Tunhsiao, a subsect of the Taokas, another Pingpu tribe from north-central Taiwan. As was usually the case, the violence was sparked by official venality, in particular, the flagrant abuses of the interpreters, a class of middlemen that had sprung up as a result of the Qing attempts to negotiate something approaching equitable land tenure agreements between Han and Pingpu.

In a well-known account of his trip to Formosa two years earlier, during which he procured sulfur from aborigines at Danshui and Beitou, the traveler Yu Yonghe (郁永河) got the chance to observe the machinations of these “village bullies”at close quarters.

“This bunch were all criminals on the mainland,” he wrote in his account, published under the title Small Sea Travel Diaries. “Fleeing from death at the hands of the law, they hide themselves in distant, out-of-the-way places uninhabited by Chinese, where they scheme to act as foremen and interpreters. With the passage of time they acquire an intimate knowledge of the barbarians and their language.”

Unlike the local tax collectors, who would be replaced on a regular basis, the interpreters “would not leave till they die.” Of course, when their antics became intolerable, this could happen prematurely, as was the case with Chin Hsien – a subordinate to the interpreter at Neibeitou. Betrothed to marry the daughter of the village headmen, he had the latter tied to a tree and flogged for delaying the marriage. The headman's family responded by murdering the official and several associates, then linking up with the Tunhsiao tribesmen, who were already in revolt, and joining them on a rampage.

Inevitably, such uprisings were swiftly crushed and, while the local mandarins were often exasperated by the behavior of the interpreters and their ilk, they usually did nothing to nip it in the bud. The bullying continued unabated, so that, in 1715, a visiting Spanish clergyman, Father de Mailla could report, “These interpreters who ought to assist these poor people, are themselves unworthy harpies who prey upon them pitilessly: indeed they are such petty tyrants that they drive even the patience of the mandarins to the verge of extremity.”1

Despite continued sporadic unrest, the writing was on the wall for the Ketagalan and other plains aborigine tribes. By the beginning of the Japanese colonial period, they had already lost a large proportion of their languages and customs. These days, the languages are all but extinct, with handfuls of speakers remaining in some of the tribes, few of them anywhere near fluent. Attempts at revivals seem doomed to failure.

According my old Pingpu pal Adawai, this is because “cultural genocide” is still in effect in Taiwan. His family are Pazeh (巴宰) –their ancestral village located in the hills of Sanyi in southern Miaoli County, a tourist town famous for its woodcarving. Only five speakers of the tribal tongue remain, several of them members of his immediate family. He's unrealistically optimistic about the chances of reinvigoration – this isn't Welsh we're talking about, much closer to the fate of Cornish.

For years, I ribbed him about this. I wasn't mocking the plight of his people: The assimilation, displacement and marginalization of plains aborigines is beyond dispute and was tragic. But the idea that a “cultural genocide” continues, I found preposterous. Aside from the limited numbers of speakers, all that remains to distinguish the Pingpu is the designations on their household registrations and atavistic cultural practices that, in some cases, totter on shaky historical ground. The assertions of noticeable physical differences are generally even more spurious. “Look at this,” Adawai says, rolling up his trouser leg. “Han Chinese do not have hair like this on their legs.”

But walking around the Ketagalan Center in Taipei's Beitou district recently, I finally found myself coming round to Adawai's point of view – or at least something close to it. For while much of Pingpu culture is now irredeemable, the authorities could at least make an effort set the historical record straight. Instead, it appears they are at best doing nothing to make information on the Pingpu available to public and at worst actively seeking to expunge their existence.

When I first visited the center, almost a decade ago, it had some displays and information, albeit limited, on the Pingpu. Now, a few sheets of paper in a display case, stuck in a corner on the third floor, opposite the toilet – that's all we have to acknowledge the existence of a people who once predominated in this part of the island.

These documents include a marriage certificate and a transfer of land rights from a plains aborigine freeholder to a Han Chinese buyer. Like Adawai, the land owner was surnamed Pan (潘), a common name among plains aborigines, especially in this area. Many Pingpu Pans were originally referred to as “Fan”(番), a word used to refer to non-Chinese “barbarians”before the water radical was added to the Chinese character to make things a bit more politically correct. According to one version of events, which Ketagalan elders have admitted is something of a founding myth, the name was bestowed on the Pingpu by a Chinese immigrant named Pan Da-lao (潘大老) with whom they were conscripted into a local militia.

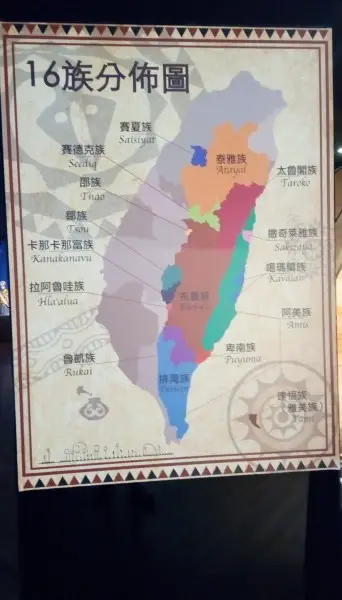

Apart from the documents, there is only a fleeting reference to “tame” aborigines or “Tongbao Pingdi (plains compatritots).” The entire space at the Ketagalan Center is occupied by displays dedicated to the 16 officially recognized indigenous groups of Taiwan, only one of which of which falls under the “plains aborigine” designation (The Kavalan from whom the name for the city and county of Yilan is derived). It seems quite incredible that a museum using the name of an indigenous people should contain no information about that people.

Imagine, by way of comparison, a museum on the Moche of ancient Peru that focused entirely on the Incas; an exhibition on Scotland's Picts, which was instead dedicated to the Celtic Britons, a center for the Antillean Arawak that contained nothing but information on the Caribs who displaced them. The situation with the Ketagalan Center is worse than any of these examples, for while there is little argument that the aforementioned peoples are now essentially extinct – exterminated or assimilated out of existence – the descendants of the Pingpu are still fighting for recognition.

It is not my purpose here to discuss the merits of the demands for Pingpu recognition and restitution. These are thorny, sensitive issues that continue to be debated by scholars, activists and politicians. They hinge in part on complicated legal issues relating to the ethnic designations on official household registrations, with activists contending that families were tricked or forced into changing these to “Han”rather than the “cooked”aborigine descriptor “shou”(熟). In recent years, several local governments in southern Taiwan made provisions for this annotation to be added to the registrations of families who could show it was on the documents of an immediate ancestor. The Ministry of the Interior swiftly moved to reverse the policy.

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2014/03/19/2003586029

As an expert and spokesperson on these issues, Adawai is among those who have helped take the Pingpu case to the United Nations. http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aedu/201008090034.aspx

For him, and like-minded activists, these are prescriptive problems firmly planted in the present; my grievance is purely descriptive and historical. The current reality of Pingpu identity might be open to debate, the historical facts are not. Either provide some information on the Ketagalan or change the damn name of the center.

On my most recent visit, the display cases with the aforementioned historical documents had been placed behind a beaded curtain and were, a member of staff informed me, off limits. (I ignored this injunction and went to snap some photos anyway.) When I asked about the lack of information on the Pingpu, a member of staff became noticeably agitated. “There are no Pingpu anymore,” she said. “They're all Chinese.”

Lest this be mistaken as an example of Han chauvinism, it should be pointed out that the woman was a member of the Paiwan tribe – one of the recognized groups. Why should my questions have drawn such a response? It could simply be that she was annoyed by the foreigner sticking his nose into issues that didn't concern him. Perhaps she felt that I was stirring up trouble for no good reason.

However, her sour-faced insistence that there was “no such thing as a Pingpu,” bespoke a different kind of resentment. Pingpu activists will tell you that their attempts to gain recognition do not sit well with many members of the recognized tribes. “It's all for selfish motives,” says Adawai. “They have been enjoying the privileges associated with recognized indigenous status for a long time and now they are scared that they will have to share the government resources with other groups,” he adds. “That's why they insist that Pingpu are not real aborigines.”

Whatever the motives, the nomenclature of the Ketagalan Center is clearly absurd. The Indigenous Peoples Cultural Foundation (原住民族文化事業基金會), a cosponsor of the center, failed to respond to requests for a comment on the issue.

The distinctive building that houses the center was once home to a military checkpoint, in the days when access to the mountain areas was restricted. (Grass Mountain Chateau, Chiang Kai-shek's first Taipei residence is up the mountain at Yangmingshan.) It stands at the beginning of Zhongshan Rd., which rises past the hot spring museum, the public open-air baths and Hell's Valley, before meeting Wenquan Rd at the top. Close by, through a rickety gate and a short climb up some steep stairs, is the Puji Temple where Guanyin and Ksitigarbha provide a testament, albeit murmured, to the hardships and dignities heaped upon Taiwan's plains aborigines. At the very least, the building at the other end of hill could do the same.

Notes

* Some sources give the killings as occurring three years apart in 1636 and 1639.

* The fort, which was rebuilt by the Dutch, the renovated and extended by the Qing and the British, who had their consulate there from 1864 to 1971, is major tourist attraction and is known locally as Hongmao Cheng (紅毛城) –Red Beard Fort.

- This and previous quotes are taken from John Robert Shepherd's indispensable work on Han-Pingpu relations Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600-1800.