With tea and preliminary chit-chat done, Diane suggests we start our tour in the large exhibition space next door. Split into sections showcasing the various series of works that have occupied periods of Hsieh’s life spanning, in some cases, a single year, in others, decades, the room provides an overview of his 50-year career. Signs on the walls and suspended from the ceiling introduce the various displays.

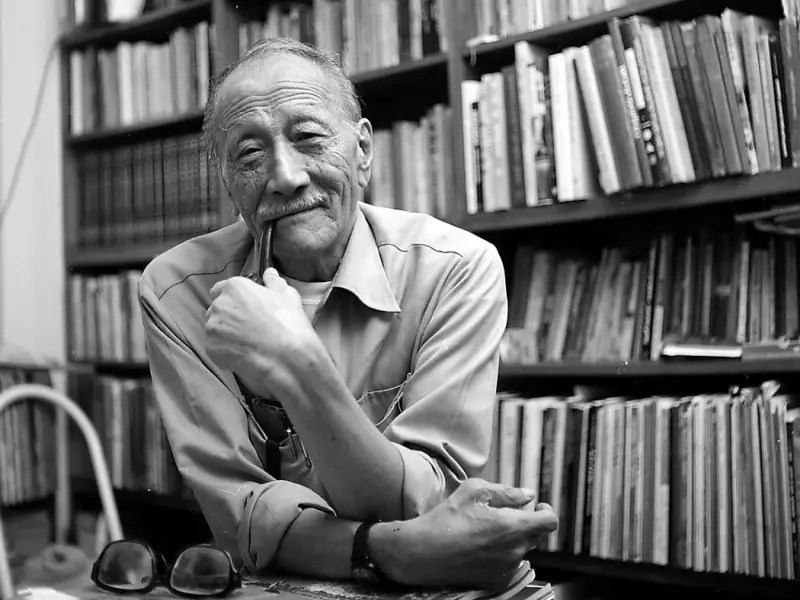

On one of the walls is a watercolor portrait of Hsieh by Max Liu, a polymath whose devil-may-care attitude and unconventional approach led to him being dubbed the enfant terrible of Taiwanese art.

Trained as an engineer, a vocation which he maintained for most of his working life, Liu did not take to the easel until he was in his late 30s. In 1964, he responded to a call from the American military for Taiwanese engineers to work in Vietnam for danger money salaries that were hard to refuse.

When he returned home three years later, he had over 200 paintings under his belt, some of them influenced by Vietnam’s Champa ruins and culture, which indicated Liu’s future change of direction toward a career as a roving cultural anthropologist who traveled extensively across Southeast Asia and Oceania.

Liu’s work is frequently found on postcards at major art museums in Taiwan. Sketches from his time in Vietnam featured prominently in the superb Secret South exhibition at TFAM in 2020, which focused on Taiwan’s interactions with and place on the periphery of the Global South.

Some remarkable coincidences link Liu to Chen Shih-ting: They were both born in Fuzhou, less than nine months apart in December 1912 and August 1913 respectively and died within two days of each other in Taiwan in April 2002.

In the center of the exhibition room, encircled by sturdy chairs of a mahogany-type wood, fashioned into indigenous tribesmen clasping cutting boards that serve as the seats, is a stone table with a chalky finish. Engravings on the sides feature the diamonds of the hundred pacer, the deadly viper whose patterns are closely associated with Taiwan’s Paiwan people. In some of the images, snake and human are merged, with the serpent’s twisting body forming pairs of bandy legs and its spearhead representing feet.

The tabletop is crammed with two dozen dusky bronze statuettes of water buffalo, their necks curved as they reach for an awkward piece of pasture. Their horned heads are instantly recognizable as a representation of the Chinese character for “ox.” Another 45 copies sit on floor next to the table. Combined with the rounded rectangles on which they are set, the U-shape of the grazing bovine creates the effect of antique clothes iron.

This latest work, from a series inspired by the traditional pictograms from which Chinese characters are derived, is unlike any other in the room, but then the same could be said for almost every series when set against any other.

“My father has already completed 18 series of sculptures,” Diane explains as she guides me through the room. “Different forms; different themes.”

The dramatic shifts in Hsieh’s creative life were emphasized in both the name and contents of a 2020 retrospective held at Taichung City Huludun Culture Center. The show, which served as that year’s Fengyuan Artist’s Invitational Exhibition – an annual spotlight on individual artists of note – was called “The Impermanence of Form”.

Artists in any field are often caught in a bind when charting new territory, whether the departure is stylistic or thematic. Those who plod along the same tried and trusted course lack originality; those who chop and change too frequently have no anchor around which to moor their evolution. Here, I am reminded of singers who have altered their sound so dramatically at different points in their career that one is left wondering what their “real” voice sounds like – if, indeed, such a thing can be said to exist.

While the notion of “impermanence of form” is taken from arcane Buddhist principles, Hsieh makes it clear in the introduction to the coffee table book that accompanied the exhibition that the notion can be used to understand the dilemma the artist faces when trying to balance innovation with style:

‘Innovation’ and ‘Style’ are invariable principles behind the oeuvre of all artists,” Hsieh writes. “These two also correlate to yin and yang in that there sometimes arises opposition and discrepancy between them. Every artist endeavors to bring these two elements into harmony. ‘Innovation’ seeks novelty and change; ‘style’ aims to retain the old unchanged. People will say you lack style if you constantly seek novelty and change, but in total absence of these, people will deem your work to be devoid of creativity.

Through tai chi and practices that aim to achieve a “middle way,” Hsieh contends, the conflicting aspects of ying and yang can be harmonized. In fact, Hsieh writes, they are not just compatible but interdependent:

There is no style without innovation; style originates in innovation. Style cannot change too quickly, nor be retained for too long. Moreover, each innovation should be imbued with one’s own style. Thus, I believe that art should be ruled by three principles: distinctiveness, variation, and meaningfulness. The first principle aims to make an artwork discernible from that of others through style. The second principle relates to the need for change. An artist should not remain inert or repeat the same work over and over again; opportunities for growth can only be found in constant transformation. The third principle requires an artwork to have meaning; otherwise, it is a mere façade or a hollow shell, unable to truly touch one’s heart.

Between 2005 and 2015, Hsieh produced three series that comprise his most abstract works: the Landscape Series, the Image Series and the Heart of Landscape Series. These tai chi- and calligraphy-inspired collections represent Hsieh’s most overt attempt at reconciling the seemingly opposing forces of innovation and style, among other ying-yang dichotomies that, according to Chinese philosophical beliefs, pervade the universe.

“Like the weather – sometimes it’s cold, sometimes hot,” he says, reiterating a point that he makes in the book’s introduction. “Light in the morning and dark at night; grass and trees grow in spring; leaves fall in autumn.”

Gliding his hand around the contours of a piece called “Sunrise (日出),” with the deftness of a wire loop game pro, he emphasizes the twin roles of color and depth in achieving contrast – again the juxtaposition of opposing but complementary elements. The work consists of a gleaming silver ball nestled in the crook of a lipstick-red “S” tipped on its side. The black undersides of the curves are speckled with thin red scribbles.

“There’s also ying-yang in color,” says Hsieh. “But in sculpture there’s often just one color, so depth is needed. If the contrasts in sculpture are not done properly, it won’t be effective.”

Like many of his works, “Sunrise” employs materials that were uncommon in sculpture when Hsieh started out: The paint is cashew lacquer – a Japanese product made from the shells of the nuts – while the sculpture itself is fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP).

“He was the first to use this in Taiwan,” says Diane, noting that Hsieh has experimented with unconventional materials throughout his career. She motions to a set of smaller works on a ledge – items from the Historical Figures Series. “These two use stainless steel wires,” she says. The pair are Su Wu and Bao Zheng, statesmen from Chinese history who have come to represent loyalty and probity respectively.

Aside from the virtues they embody, it’s easy to see why Hsieh might have chosen them as subjects, particularly in this medium. Both men are identifiable by the attire in which they are commonly depicted – indeed, the works are much more sweeping garments than human forms, enabling Hsieh to better showcase the wire mesh technique he has used.

Su Wu, who was supposedly banished by his Xiongnu captors to Lake Baikal where he tended sheep, dons a billowing cloak with the crumpled hood exaggerated into a leaf shape. From the left fold of the cloth, the two ends of a rod protrude – the one-time imperial staff, now shepherd’s crook, a symbol of fealty that the erstwhile diplomat preferred to temporarily degrade rather than relinquish.

As for Bao Zheng, the preposterously long flaps of his trademark Zhanjiao Putou hat are realized with simple elegance through a single spindle of wire. According to legend, this bizarre headwear was introduced by Song Dynasty founder Emperor Taizu (宋太祖) to keep his chattering officials apart during official business – social distancing a millennium before it became fashionable. In his tiny, clenched fist – essentially just an extension of his open cape flap – Justice Bao clutches a scroll, presumably detailing one of his famously impartial decrees.

Before we adjourn to the yard for the much-anticipated tour, Diane shows me some of the commercial works that her father has produced in cooperation with Chungyo Department Store in Taichung’s North District.

Since a well-received 2012 exhibition in Shanghai, Diane, who teaches art design and creative industries at Taichung’s Chung Hsing University and National United University in Miaoli City, has worked as Hsieh’s agent and curator for his shows.

“The motive for me helping him was that I was moved by the response to my father’s work,” she says. “Especially from Westerners – French, Italian visitors … That’s why I became his agent.”

With a clear appreciation of marketing, Diane is forthright about exploring more commercial opportunities for her dad and, while attempts at gaining exposure in Europe have not yet borne fruit, she is enthusiastic about the potential for further partnerships with well-known enterprises such as Chungyo.

“They have an art gallery in the store, so I contacted them to hold an exhibition of my father’s works,” she says. “After that, they began using his sculptures as gifts for manufacturers and producers whose revenues [for the store] are over NT$10 million.”

As with most artistic sculptures, there is a limited number of casts. “This one has six,” she says, removing a pint-sized Guang Yu figurine from a presentation box by way of demonstration. “Some of the others have up to 12 copies. It depends on the level of the company.”

Although this kind of production-line cobranding is something of a departure from Hsieh’s previous work, commercial projects are nothing new to the artist. “When I was a child, my father couldn’t sell his art,” says Diane as we step outside. “People didn’t really understand it then; it was too contemporary. So, he had to do this kind of stuff.”

Indeed, many of the statues outside represent what Diane calls “selective, memorial sculptures” for private individuals. Some are of relatively obscure public figures. To the right of the door to the yard, for example, there’s a severe-looking, bespectacled fellow, clad in a chángshān robe. Hands folded, atop a cane, he grimaces like a history teacher disgruntled by a particularly inane answer.

“Dad, who’s that?” Diane asks, noticing my interest.

“Lu Shih-ming– Changhua County Magistrate in the early 1960s,” Hsieh replies. “A lot of those government officials wanted me to do sculptures of them.”

Further along the wall, incongruously placed behind the outstretched assault rifle of a combat-helmeted soldier, is an altogether more benevolent looking figure. This is Lee Yuan-tseh (better known in the English-speaking world as Yuan T. Lee, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1986. “That was just after he’d become President of Academia Sinica,” says Hsieh, referring to Taiwan’s national research institution. “He came here, and I did that for him.”

Some of the works have a more personal significance. The pigtailed girl peeping from the pillar, who I’d noticed during my initial reconnaissance, turns out to be a 10-year-old Diane. A companion piece of her elder sister, dressed in a loose blouse that hangs over her bare thighs, can be found leaning against a wall round the back. Beside an irregular oval window onto the exhibition room, dressed in what might uncharitably be described as a “wife-beater,” Hsieh’s father stoops with a tennis racket in mid-backswing.

“He played for 86 years – from 11 years old until he was 97.” says Hsieh.

On a shingled area near an iron gate that marks the division between the two buildings, is small sculpture hewn from a craggy lump of rock. It depicts a couple seated on a bench. An air of great contentment is palpable in their demeanour, the round-faced woman concentrating on something her partner is saying, as the latter, a moustachioed man in a fisherman’s beanie, slouches back in his seat, a cup of something held against his belly.

“Ju Ming and his wife,” says Hsieh.

It takes me a second to register. One of Taiwan’s most famous artists, Ju Ming is probably best known for his Taichi Series, comprising 62 chunky, angular pieces featuring martial arts practitioners in various poses. Copies can be seen all over Taiwan.

“A good friend of my father,” Diane says. It’s not hard to see why they would be kindred spirits.

There are also the grander, more famous works – the ones that first attracted my attention. These are the pieces upon which Hsieh’s reputation was built and cemented.

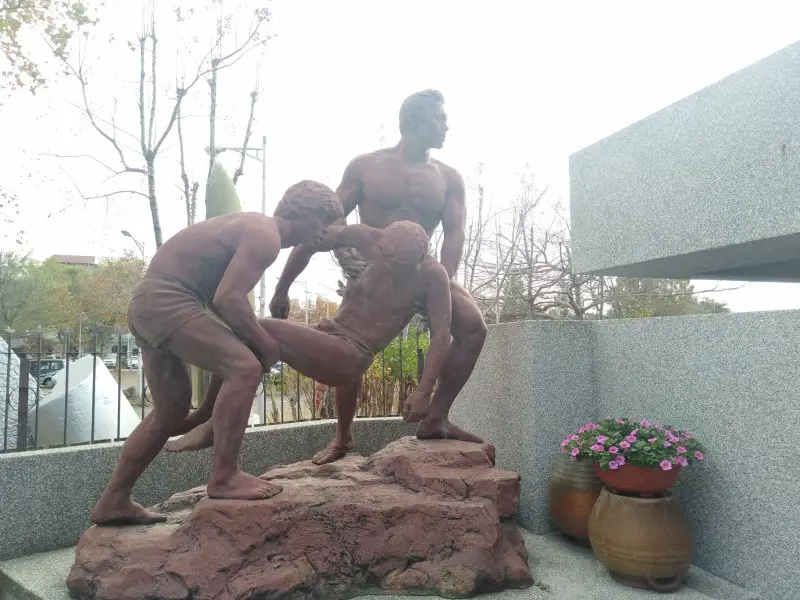

The elongated lady from TFAM is a piece from 1984 called, in English, “Look Forward”; the man in the rice hat sheltering the youth is “Walk with Me”, which is part of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts Collection in Taichung; and the sculpture of the muscular duo heaving their unconscious companion, which has been translated into English literally as “On Ancient Path” and prosaically as “Rescue of Coal-Mine Victim” can be found outside New Taipei City Gold Museum at Jinguashi. Completed between 1980 and 1981, these latter two works tail-ended the Realistic Series with which Hsieh began his career as a 20-year-old in 1969.

Other important pieces include the fragmented figures from the Impermanence Series (1997-2002) that lent its name to the 2020 retrospective. Inspired in part by the 921 earthquake of 1999, the cracked torsos and torn limbs of these works add a new layer of meaning to the theme that inspired the exhibition.

Just as we are about to enter the the beating heart of the complex – the workshop, which is housed in the building with the distinctive façade – Hsieh’s wife appears bearing gifts. She has just returned from Donghai Arts Shopping District, looking pleased as punch with her purchase – another trilby to add to hubby’s large collection, this one red with a band of sandy beading and white trim.

“It was a really good deal!” she beams, as Hsieh tries it on for size. It’s easy to see from this interaction and the images I find of them attending events together that they are an affectionate, tactile pair, with none of the reserve that marks the relationships of some aging Taiwanese couples.

Clearly happy with the present but saving it for a better occasion, Hsieh takes it off to replace it with his cap. Before his wife can retrieve it, Diane grabs the hat and turns it over to look at the price tag which is still attached.

“Four hundred and ninety, mom?”

Her mother shrugs sheepishly. “They have good stuff there,” she says.

It seems reasonable enough to me. “You can get the same thing at Carrefour for cheaper,” Diane whispers dismissively.

Inside the workshop, I get a sense of the artistic process. It’s suitably cluttered and chaotic, with works – completed and in progress – in all corners. On several easels, stainless steel wire rods bound to pieces of wood have been contorted into skeletons that await clay flesh. Materials of all shapes and sizes lie everywhere – plaster, wood, stone, metals and FRP.

Diane has to excuse herself. “I have a flute class,” she says. “I’m trying to combine it with tai chi performance.” She insists that I stay as long as I want to, though it is indeed getting late, and I am hoping to visit the Chen Ting-shih museum and put in some miles before dark.

With Diane gone, Hsieh invites me to wander around. He delivers a monologue, his voice soft and diction slightly slurred. I don’t catch all of it, but it appears to be an explication of the paradox of commercial vs. artistic work.

“With the commercial, it’s sometimes more outwardly complex, but the meaning is simple,” he says. “Conversely, with the abstract stuff – the real art – the form is simple, but the meaning is complex.”

As he speaks, I step into a small extension of the main studio. There, in red clay, raised up on a platform supported by breeze blocks, is a life-sized sculpture of Chiang Kai-shek seated in a hefty armchair.

Earlier, as we toured the exhibition room, Hsieh had pointed out some photos from ceremonies he had attended in China and Japan, the latter hosted by the Japan-China Friendship Association, to unveil statues of Chiang that he had created. (It is not that widely known that Chiang served in the Imperial Japanese Army, even less so that he continues to enjoy a decent reputation among many Japanese because of his magnanimous treatment of their countrymen in China after the war.)

“Have you been up to Daxi?” Hsieh had asked me, referring to the Cihu Memorial Sculpture Park in that district, where about 150 CKS statues reside. I’d confirmed that I had, having made a spontaneous detour during a previous Lunar New Year’s bike trip with a mate several years earlier.

“About a quarter of those statues are mine,” he says. “Some were from parks, but a lot were just lying around. What was I going to do with them?”

Old Peanut has an expression of smug benevolence pasted on his mug. It occurs to me that almost every effigy is like that, in contrast to his stern reputation. “One day, I’d like do him looking serious,” Hsieh murmurs, as if reading my mind.

As an artist and native Taiwanese (benshengren) who, like many Taiwanese, personally knew people who suffered under the White Terror, I’m curious how Hsieh feels about having contributed to this cult of personality.

He shrugs. “I needed the money.”

Before I head off, Hsieh’s wife insists I sit down and have some fruit back in the living room. A friend has arrived, and they are nattering away in Taiwanese Hokkien. Seeing I haven’t the foggiest what is being said, they try to teach me an idiom. I can’t remember for the life of me what it was.

“Taiwanese is much more beautiful for expressing creative concepts,” says the visitor. “But the curse words are much more vulgar!” She cackles. “It’s simple but expressive.”

An enigmatic smile flickers across Hsieh’s lips.

“Ying and yang again,” he says. “Real art is inexpressible – less is more. Like a simple poem. The words are simple, but we have to dig to get at the hidden meaning.”